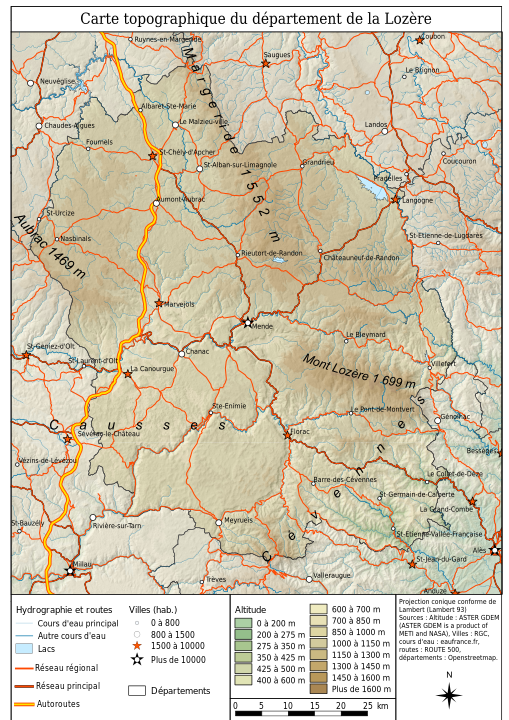

Even to a French person, the names of towns and villages of Lozère and Auvergne (the two principal regional theaters of the attacks of the Beast), can be quite confusing, really only evocative to those locals who happent o know every single hamlet in their neighborhood. And since, then and now, this particular region of France remains sparsely populated, that leaves a great many people wondering: “but where exactly was that thing active?”

What does the region of Lozère look like?

rivers and villages, by Etienne Baudon.

The main location to keep in mind when thinking about what used to be Gévaudan is the town Mende, the prefecture of the department of Lozère, in the region of Occitania. The city itself dates back to 200 B.C., is located roughly between Clermont-Ferrand and Montpellier, with a whopping 12,000 inhabitants. That should give you an idea as to just how sparsely populated the region truly is.

Mende is located in the area known as the Grands Causses, one of four mountain ranges of Lozère (the other three being: the Margeride mountain, the Mont Aubrac and the Cévennes). Like most other towns and villages in the area, Mende is nestled amongst valleys, mountains, hills ans creeks. As it stands, Mende may be the principal town of the region but it was not really where the Beast liked to prowl, preferring instead the area of the Margeride, where most of its victims were killed.

I do not mention these various “monts et montagnes” (as we say in French) simply for the fun of it: the rough terrain of the region made it especially difficult to track and hunt the Beast in the 1760s. Those “chasses générales“, as they were called, had to be carefully organized in an otherwise unpredictable terrain, with dense woods, rivers, creeks and harsh winters.

Mapping the epicenter of the attacks

Using the software uMap, an OpenStreetMap project hosted, among many others, by University College London and Umeå University in Sweden, I went ahead and pinpointed the known locations of recurring attacks on civilians during the years 1764-1767. The map is divided into two layers (so far, more may be added in the future): the first layer displays the places where the attacks took place based on the reports of the Courier d’Avignon, L’Année Littéraire and other contemporary sources ; the second layer displays the locations of places mentioned either by the author or contributors (i.e.: “Letter from Montpellier, January 1764″). These have no particular bearing on my research other than to exemplify the range of publication of reports about the Beast of Gévaudan.

Obviously, there are some limitations to contend with when mapping an area which, despite its sparse population and mostly rural environment, has undergone many changes since the end of the 18th century. The first and most obvious one being the inevitable changes in the names of towns and villages, to say nothing of what we call “lieux-dits” (localities), which may have lost their 18th-century names, been destroyed or abandoned and now only live in local memory. These sites are extremely hard to find and some may therefore not have been added to the map in an effort to avoid any confusion.

Any and all locations pinpointed in the map above will in any case appear in a specific index page on the website, with some more information regarding their location and history, so as to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the area.