As part of our thesis project, students from the Rare Books & Digital Humanities Master were also expected to create a “digital object”. That “object” could take many forms, from a simple timeline to a complex Twine story. In the context of my research, I chose to create a computer-readable edition of the Magné de Marolles Recueil factice from 1765.

In order to do so, I used the well-known software Transkribus, used by scholars, students, researchers and enthusiasts all around. The reason behind this choice was simple: I was already familiar with the platform and it is one of (if not the) leading transcription platforms.

Since the Recueil factice is an assortment of printed newspaper clippings and handwritten text, I chose to transcribe only the handwritten portions, since out of the 255 pages digitized by the BnF (not counting prints), only 43 consist of printed material while the rest was entirely transcribed by hand. The reasoning behind this was to create an OCR’d document that anyone could easily research and pull keywords from using the good old Ctrl+F method. As I explain in my thesis, making a historical text more available to the wider public (in whatever manner) eventually gives meaning back to the source material itself. Pulling manuscripts that have been largely forgotten about from their proverbial dusty bookshelves marks the first step in creating a relationship between a document and an audience, whomever that audience may be.

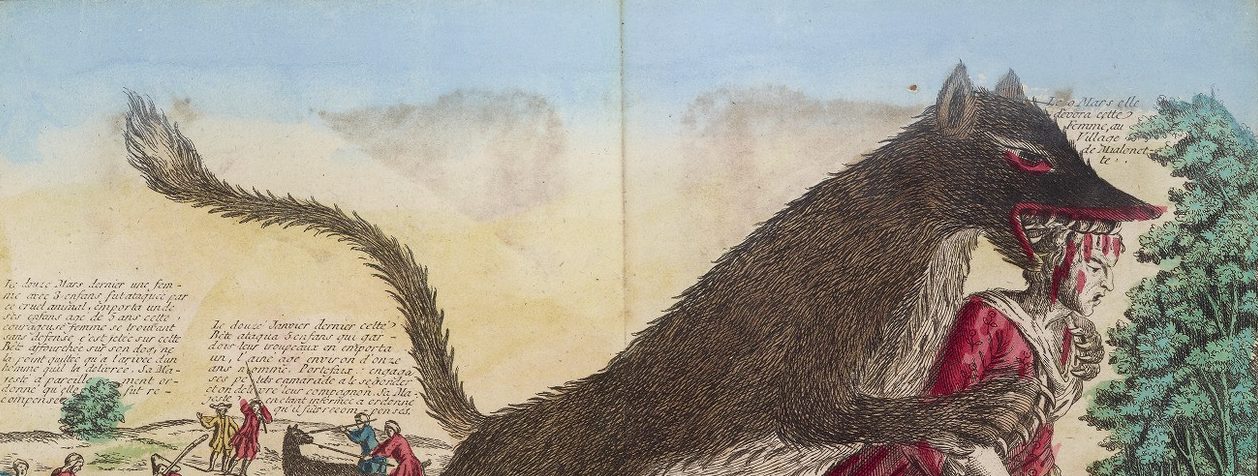

The Magné de Marolles Recueil factice is one such document. Although referenced by many authors who have written extensively about the beast of Gévaudan, it has never been used to its full potential. Transcribing it, and turning it into an easily exploitable text file for readers to pull from, brings it one tiny step closer to this goal. In the context of this particular research, the transcription of the Recueil was necessary in order to pull keywords and phrases relating to the imagery of “la bête féroce” (as it was known).

The transcription process

(Disclaimer: The following text is taken directly from my Master thesis, from Chapter 3, section 3.2.2., pp. 49-53.)

Transkribus text analysis models

In order to carry out the transcription, the first step is to choose an automatic text recognition model, of which Transkribus has hundreds, modeled on specific languages, from specific time periods, specific formats (printed or handwritten). For the first few pages, the model “Transkribus French Model 1” (TFM1) was used to establish accurate ground truth data. This model was pre-trained on the platform, and is tailored to handwritten French material spanning the 17th to the 20th centuries. Gathering accurate ground truth data is the first step in any transcription process: it is the very first building block of the entire operation and the result of careful manual correction of the automated transcription, in order to rectify any mistakes and train the model further in recognizing where those mistakes might occur again to prevent that from happening.

Once enough ground truth data has been acquired (i.e.: manual transcription), ideally, the second step would be to create a personalized transcription model, to ensure that the automated portion of the transcription becomes even more accurate, thus limiting the need for manual correction and re-transcription when mistakes occur. In order to do that, a first model called “Handwritten 18th-century French” (H18F) was created. Based on roughly 8000 transcripted (and corrected) words from the Recueil, it still had a high error rate, but managed to automatically rectify many of the mistakes that TFM1 made, without the need for much human intervention. Given the success rate of a personalized model versus TFM1, a second, even more efficient model was created, called “Neat Handwritten 18th-century French” (NH18F), as a node to the incredibly neat and precise hand of the author of the Recueil, which, in its own right, certainly made the entire transcription process much easier. This model was trained on some 24,000 words worth of ground truth data, making it incredibly efficient, with a much lower error rate than its predecessor. Automatically transcribing the Recueil using this model took perhaps half the time it would have otherwise, with very few mistakes here and there requiring human intervention.

Transkribus layout analysis

The other thing to consider when transcribing any document is the layout of said document–particularly in the case of handwritten historical documents. But what does layout actually mean? The layout of a given document refers to its internal structure: how the words are arranged into different sections on the page. In fact, Transkribus refers to paragraphs, titles and footnotes as “sections”. Tailoring the right layout to a document is an important step in the transcription process, as it will help ensure maximal results when the automated text recognition starts. In fact, ideally, it should be the first step in any transcription process. Establishing the layout of a page ahead of transcription helps avoid mistakes such as: run-on lines, bisected lines, forgotten lines, line transference from one section to another, problems with word and line order, etc.

In the case of the Magné de Marolles manuscript, its internal layout made it quite difficult to work with. While on some pages, organizing sections of text for Transkribus to recognize was easy enough, that was not the case for the majority of them. Aside from the table of contents and title page with the sprawling marginalia (obviously difficult cases), it seems that de Marolles was very fond of using “footnotes” as a sort of punctuation to his own transcription of contemporary newspaper clippings. The term “footnote” here is used in-between quotation marks because these are not, in fact, the traditional footnotes found in scholarly essays (which was certainly de Marolles’ original intent).

Instead, the author used “floating” footnotes next to his main text, in the margins, to either add details on a particular point or, as was the case most often, reiterate in an abridged version what he had just written. This peculiar mechanism almost gives these margin footnotes a timeline-like quality: each of them peppers the main text, picking up the facts that were of the most interest to the author, giving his text a certain rhythm and acting as a chronological timeline of the events recorded in the compilation. As the transcription process continued, one can almost repeat verbatim what the next footnote is going to say, solely based on reading the main text and the knowledge of how the previous ones were written. Magné de Marolles used these notes to point the reader towards the important parts of the story. But, originally, by his own admission, the Recueil was meant for himself, so what were these notes for? Were they added afterwards, once he had decided to give the Recueil to the national library? Or were they for his own benefit, so that he could go back to them should he need information on the fly, rather than have to dive back into the main text?

In regards to transcribing, the decision was made to transcribe Magné de Marolles’ marginal notes into modern-day footnotes, for ease of comprehension and clarity, as well as logic. Although different in style to what our understanding of a footnote is today, de Marolles clearly intended them as such–or at least, to serve in the way that we modern readers might understand a footnote. Unfortunately, by choosing to transcribe them in that way, the rhythmical, timeline-like, quality they gave to the original text is greatly diminished. No longer punctuation to the text, pointing out to the readers where their eye should be directed, they are now relegated to the margins (quite literally). It would have taken a great deal of time and effort to recreate the exact layout of the Recueil, floating margins and all, and as such was not a realistic prospect for this particular project. It is, however, something that would certainly be worth looking into once the transcription process is complete.

Aside from the footnotes, the layout of the manuscript is fairly straightforward and, as such, relatively easy to transcribe: the Recueil mainly consists of titles and subtitles and the main body of text. Added to that is the fact that de Marolles possessed a very neat hand and used very few abbreviations, in turn making it easier not only to understand him, but also for the automatic transcription model to accurately transcribe him. For example, the only recurring abbreviation he routinely used was to shorten the word “paroisse” (parish) to “psse”, with a looping tilde above the double “s” to signify the truncation of the word. In the raw transcription carried out on Transkribus, the abbreviation was kept as such, minus the tilde, but in the final, modernized transcription, the word will be written in its full length.

Had the Recueil been compiled a century earlier, things would certainly have looked quite different, since 17th-century handwriting is notoriously difficult to decipher and usually requires the intervention of a skilled paleographer. But de Marolles was highly educated, a scholar, and, most importantly, writing for the specific purpose to keep this record of the events in Gévaudan for posterity, which demanded a certain degree of dedication–something he possessed in more than sufficient quantity–as well as adequate penmanship.

While the layout of the Recueil factice already tells us quite a lot about the intention of its author, the text itself, aside from the Précis historique, which de Marolles wrote himself to summarize the facts, was obviously not written by him, but rather, transcribed by him into manuscript form. The collection of letters and newspaper items he compiled together tell us another tale: that of a ferocious beast preying on the children and defenseless women of Gévaudan, attacking in broad daylight, with a description to match its diabolical nature.

(End of text taken directly from the thesis.)