The lexicon surrounding the beast of Gévaudan: the attacks on young Portefaix and Jeanne Chastan

Before looking more closely at the lexicon employed in the compilation of the Receuil factice, there is one question that we must ask ourselves: why are we so fascinated by gruesome stories and monsters? What draws us back to those stories time and time again, despite our simultaneous aversion to their subject-matter? What is it about monsters that draws us in?

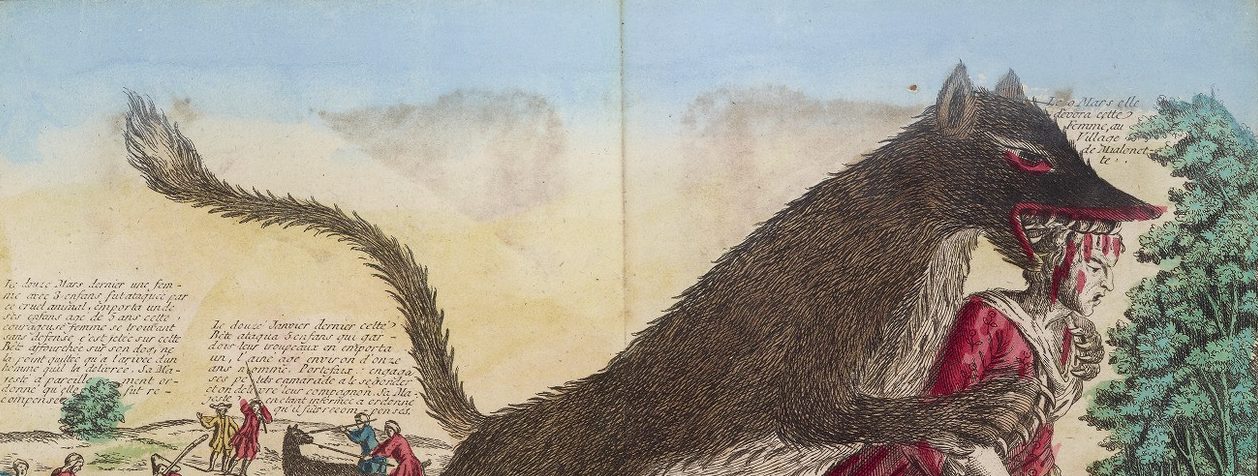

According to Noël Carroll in The Philosophy of Horror, we don’t actually love monsters themselves, but we love to see humans contend with them: how do the protagonists deal with the monster? Will the heroes win or be killed? Will the monster be defeated?1 In the case of the beast of Gévaudan, there were two instances in particular where La Bête found her match, and readers of the Courier d’Avignon and the Gazette de France were given an epic tale of heroes battling the monster of Gévaudan, both compiled within the Magné de Marolles Recueil factice: the tale of the little Portefaix and his friends, and the story of Jeanna Chastan, who fought tooth and nail to protect her children.

Interestingly, a simple automated search of the manuscript returns that the word “monstre” (monster) is only used three times to refer to the beast directly, however, another word comes up time and time again: “féroce” (ferocious). Using a keyword search function through a Python script via Google Colab to find out exactly how many times the word “féroce” comes to define the word “bête”, the return integer is a staggering seventy-seven times. In other words, the word “bête” is directly attached to the word “féroce” almost eighty times throughout the entire transcripted document. In order to narrow down the field of possibilities, Python was instructed to find words specifically related to the keyword “bête” within the same sentence or paragraph, making the recurring occurrence of the word “féroce” even more prevalent, since it appears to be consistently linked to the beast.

Additionally, the verbs “attaqua/attaqué” (attacked), “dévora/dévoré” (devoured) come back eleven and ten times respectively, next to the word “ravages” (ravages, destruction), which comes back thirteen times. The word “sang” (blood) also appears ten times, to describe the scenes of the attacks, but also when the beast herself is wounded. The occurrence of specific words within the document can also be checked via a simple search function on the raw transcription of the Recueil.

How were the confrontations between this “bête féroce” and our two heroes, Portefaix and Jeanne Chastan, related? What was the vocabulary employed to create a contrast between the victims and the monster attacking them?

The tale of the young Portefaix, January 12th, 1765

(All quotes are pulled directly from the raw transcription of the Recueil factice, and translated into English for ease of comprehension. See footnotes to find the original.)

On February 18th, 1765, the Gazette de France reported on yet another attack, which happened almost a month earlier near the parish of Chanaleilles (Haute-Loire). Five young boys and two girls, out guarding cattle, were viciously attacked by the beast and fought to keep her off of the youngests amongst them. The Gazette report copied in the Recueil factice is as follows:

On January 12th, she [the beast] attacked five little boys from the village of Villeret, from the parish of Chanaleilles. The three oldest were around eleven years old; the other two only eight, and they had with them two little girls around the same age. These children were guarding cattle up high in the mountain, each armed with a stick to which they had attached a pointed iron blade of a length of about eighty fingers.2

The battle ground is already delineated: the children, armed with the makeshift spear that was the only protection shepherds had against wolves at the time, were up alone in the mountains, trying to preserve their families’ livelihoods (cattle), when the beast struck. Using the mountainous terrain to her advantage, it seems she eventually got close enough to launch her attack:

The ferocious beast came at them, and they only saw her once she was very near them. They came together as quickly as possible and positioned themselves in defensive positions. The Beast circled two or three times around them before pouncing on one of the smallest boys. The three oldest lunged at her, stabbing her multiple times without ever piercing her skin.3

Here we have that word almost always associated with the beast: “ferocious”. That she is ferocious, there can be no doubt, given the account of how she managed to not only see which of the children was the easiest prey, but took her time in doing so, circling around them before making her move. The vocabulary used here is telltale of predator versus prey, outlining the seemingly hopeless situation the children found themselves in, armed with their little sticks that seemed to have little to no impact on the beast.

However, keeping at it, they managed to get her to let go: she moved away after tearing out part of the little boy’s right cheek, which she had grabbed, and began to eat this little bit of skin in front of them. Soon after, she attacked the children again with renewed ferocity: she caught the arm of the smallest of them and took him with her. One of them, horrified, told the others that they should run whilst she devoured the one she had just taken, but the oldest, named Portefaix, who was always the leader of the band, told them they had to deliver their friend or perish with him.4

The beast only gets more vicious, tearing off skin and proceeding to eat it in front of her victims, while the children desperately try to keep her at bay. The coded vocabulary of predation is even more prevalent here, with the added contrast of the complete dehumanization of the victims, whose names are not mentioned (aside from Portefaix), but whose bodies are lacerated. The victims become the sum of their parts: a bit of cheek here, an arm there, until death ensues and their remains are strewn about the countryside for others to find. The beast becomes the eponymous monster who devours the anonymous masses, discarding them after she’s had her fill, leaving only fear and horror in her wake.

But that was without counting on the clear savior of the day: Portefaix.

[…] They then went after the Beast, pushing her into a bog […] where the terrain was so soggy, she sank up to her stomach, which delayed her retreat and gave them the time to get to her. Since they had noticed they could not pierce her skin with their makeshift spikes, they tried to wound her, going for her head and especially her eyes. […] During the fight, she still had the smallest boy tucked under her paws, but she had no time to bite him since she was too preoccupied with trying to dodge his friends’ repeated attacks. Finally, the children harassed her with such consistency and fearlessness that they made her let go a second time and the little boy she had taken emerged safe other than a wound on his arm and cheek.5

Here the landscape of Gévaudan plays a primary role in the tale, helping the children defeat the monster attacking them, until they finally emerge victorious. The bog helps them trap the beast, giving their little friend a fighting chance he would otherwise not have had, had the beast managed to drag him further into the woods, as he had done with previous victims. The boggy terrain forms part of the tale, further underscoring Walpole’s evocative notion of a Gothic monster suited to a Gothic landscape, with heroes fighting it off against all odds.

In the end, the story concludes thus, when a man, hearing the children’s screams for help, rushes to the scene and the beast “hearing a new foe, stood back on her rear legs, and having seen the man running towards her, fled […]”. We are then told that she went on to kill a fifteen year old boy further away and attacked a young girl, who fortunately survived, which was not the case of another woman she attacked later on, whose headless body was found. Again, the victims are not named, only the horrifying details of their deaths are recounted. The behavior of the beast, lunging up on her hind legs, is also uncharacteristic of a wolf, but rather reminds us of a bear, although she was never described as such. This is one example of how the beast does not appear to behave as she should, so to speak, compounded with the fact that her skin appears to be thick enough to rebuff attacks.

This particular tale of Portefaix and his friends has a happy ending, almost like a fairytale, in which the heroes not only survive, but are handsomely rewarded for their effort. The King, having heard of their exploits, gave four hundred pounds (400 ₶, which is the symbol for the “livre tournoise” currency) to Portefaix and a further three hundred pounds to his little comrades. In point of fact, Portefaix is cited by name (unlike many of the other victims attacked by the beast) another six to ten times in the Recueil factice, outlining the importance of his story within the larger tale of the beast of Gévaudan.

Another story, also relayed by the Gazette de France and copied in Magné de Marolles’ manuscript, garnered nearly as much attention: that of the young mother, Jeanne Chastan, who fought off the beast in a desperate bid to save her children.

The story of Jeanne Chastan and her children, March 14th, 1765

Nearly a month after the unsuccessful attack on the young Portefaix and his friends, La Bête struck again, attacking a young woman, at home in her garden, and attempting to make off with her eldest.

The 14th of this month [March], a woman from Rouget, standing with her children by her garden at around noon, was attacked by the ferocious beast, who pounced on the eldest of those children, about ten years old, who had in his arms the youngest, still at the breast. Their mother, terrified, went to help her two children, and took them each by turn out the animal’s jaws, who went for one when the other was reclaimed from her. It was the youngest she attacked the most relentlessly.6

In this story, not only do we have a beast who attacks children, but attacks them while in the safety of their home, right in front of their mother. The term “ferocious” makes a comeback, set against the vulnerability of the youngest child, probably an infant, “still at the breast” and completely unable to defend themselves. The word “jaws” (“gueule” in french) also serves to further amplify the predatory behavior of the attacker.

Finally, seeing that her prey were being taken from her, the ferocious Beast furiously pounced on the third child, about six years old, whom she had not yet attacked and whose head she engulfed in her jaws. The mother ran to their help, and after trying unsuccessfully to stop this animal, she climbed up on its back, where she could not manage to hold on for very long. As a last resource, she tried grabbing onto the beast […] but, her strength failing her, was forced to let go and leave her child at the monster’s mercy.7

Here, for the first time, we see the beast referred to as a “monster”, foiling the poor mother’s efforts to protect her children. The phrase “engulfed in her jaws” (in french: “engloutit dans sa gueule”) is also horrifically evocative, especially given the fact that the beast went for the child’s head, signifying that the contrast in their strengths was about to take an even darker turn, probably resulting in the severing of the head, a killing blow the beast had been renowned for already prior to this attack and which further dehumanized its victims.

Once again, a man came to their rescue, and his dog managed to force the beast to let go of the child, not without butting heads with her first, who apparently launched him in the air before fleeing the scene. The description that follows plays up the sense of horror, describing the child’s wounds in a very gruesome manner, almost with the precision of a surgeon:

The child she [the beast] had let go of has the upper lip torn off, the cartilage of the nose entirely eaten, a cheek torn off, and what is most dangerous of all, the skin of the skull taken off, falling right and left on his shoulders. There is everything to fear. We can only imagine the state of the poor mother at this macabre picture; she came overwhelmed with weariness, her face drenched in tears of tenderness and pain, and her heart torn between joy at saving two of her children and despair at seeing the third so cruelly mutilated.8

Once again, we see a clear narrative contrast between the horrifying description of the little one’s wounds, who might not survive them, given their severity, and the description of his (or hers) mother’s tears. The reader is in turn horrified and then moved by such a compelling tale of motherly love, bravery and monstrousness, all mixed into one. Just like Portefaix and his friends, although the ending appears less happy, Jeanne Chastan’s bravery and tenacity was lauded, and she herself received a reward from the King. Therefore, although this tale seems more bittersweet, given the state of one of her children, unlikely to survive long, the hero still managed to emerge victorious, saving the rest of her children from the monstrous beast.

So well-known (thanks to the effort of the Gazette) were the tales of Portefaix and Jeanne Chastan that two poems were even written about their story. Magné de Marolles included both in his Recueil factice, printed as they were at the time. Not only do we have well-narrated tales of woes found in the press, but those same tales even inspired their own ballads, further strengthening the position of Portefaix and Jeanne Chastan as heroes who triumphed over a monstrous opponent. Indeed, the first poem, inspired by Portefaix’s story, reads: “Le Triomphe de l’Amitié, poème héroïque. En deux chants”; while the second read “Le Triomphe de L’Amour Maternel. Poème héroïque.”

Jeanne and Portefaix’s tales of bravery, although no doubt partially true, were certainly crafted to keep the readership of the Gazette interested in La Bête. The narration, in both cases but especially in Jeanne Chastan’s case, shared between horrifying elements tied to the killer and its actions, and the tenacity of those who opposed it, crafts a compelling tale, employing vocabulary that leaves no doubt as to the monstrosity of the beast, as felt by the inhabitants of Gévaudan themselves, witnesses to its attacks, and by those who read about them from afar. La Bête, then, became a monster in her own right.

- Noël Carroll, The Philosophy of Horror, quoted in: Jeffrey Weinstock, The Monster Theory Reader, (2020): 19. ↩︎

- In french in the text, taken from the raw transcription of the Magné de Marolles Recueil factice: “[…] Le 12 Janvier elle attaqua 5 petits garçons du village de Villeret psse de Chanaleiller. Les trois plus avancés avoient environ 11 ans; Les deux autres n’en avoient que 8, et ils avoient avec eux deux petites filles environ du même âge, ces enfans gardoient du Bétail au haut d’une montagne; ils s’étoient armés chacun d’un baton au bout duquel ils avoient attaché une Lame pointüe de fer de La Longueur de quatre vingt doigts.” ↩︎

- In french in the text: “La Bête féroce vint Les surprendre, et ils ne L’apperçurent que lorsqu’elle fut près deux. Ils se rassemblerent au plus vite et se mirent en deffense. La Bête Les tourna deux ou trois fois et enfin s’élança sur un des plus petits garçons. Les trois plus grands fondirent sur elle, La picquerent à plusieurs reprises sans pouvoir lui percer la peau.” ↩︎

- In french in the text: “Cependant à force de la tourmenter, ils Lui firent lâcher prise: elle se retira à deux pas aprés avoir arraché une partie de La joüe droite du petit garçon dont elle s’étoit saisie, et se mit à manger devt. eux ce Lambeau de chair. Bientôt après elle revint attaquer ces enfans avec une nouvelle fureur: elle saisit par le bras le plus petit de tous, et L’emporta dans sa gueule. L’un d’eux épouvanté proposa aux autres de s’enfuir pendant quelle dévoirait celui qu’elle venoit de prendre; mais le plus grand nommé Portefaix qui étoit toujours à La tête des autres Leur cria qu’il fallait délivrér leur camarade ou périr avec lui […]” ↩︎

- In french in the text: “[…] ils se mirent donc à poursuivre la Bête et la pousserent dans un marais qui étoit à 50 pas, et où Le terrain étoit si moû qu’elle y enfonçoit jusqu’au ventre; ce qui retarda sa course, et donna a ces enfans Le temps de la joindre. Comme ils s’étoient appercus qu’ils ne pouvoient Lui percer la peau avec leurs espèces de piques, ils chercherent à La blesser à La tête et surtout aux yeux […] Pendant le combat, elle tenoit toujours Le petit garçon sous sa patte, mais elle n’eut pas le temps de le mordre parcequ’elle étoit trop occupée à esquiver les coups qu’on Lui portait. Enfin ces enfans la harcelerent avec tant de constance et d’intrépidité qu’ils lui firent lâcher prise une seconde fois, et Le petit garçon qu’elle avoit emporté n’eut d’autre mal qu’une blessure au bras, et une Légére égratignure au visage.” ↩︎

- In french in the text: “Le 14 de ce mois une femme de Rouget# étant vers le midi avec trois de ses enfans sur le bord de son jardin fut attaquée brusquement par La Bête féroce qui se jetta sur l’aîné de ces enfans aâgé de 10 ans, lequel se tenoit entre ses bras le plus jeune encores à La mamelle. La mere épouvantée alla au secours de ses deux enfans, et les arracha tour à tour de la gueule de cet animal, qui Lorsqu’on Lui en etoit un se saisissoit de l’autre. C’étoit surtout le plus jeune qu’elle attaquoit avec le plus d’acharnement.” ↩︎

- In french in the text: “Enfin voiant qu’on Lui enlevait ses deux proies, La Bête féroce alla se jetter avec fureur sur le 3e enfant agé de six ans ou environ qu’elle n’avait pas encore attaqué et dont elle engloutit la tête dans sa gueule. La mère accourut pour le défendre; après avoir fait des efforts inutiles pour arrêter cet animal, elle monta à califourchon sur son dos, où elle ne pût se tenir longtemps; pour derniere ressource elle chercha à saisir La Bête […] mais Les forces lui manquant tout à fait elle fut obligée de Lâcher prise et de Laisser son enfant à La mercy du monstre.” ↩︎

- In french in the text: “L’enfant qu’elle avait Laissé a La Lèvre superieure emporté Le cartilage du nez entiérement mangé, une joüe déchirée, et ce qu’il y a de plus dangereux, toute La peau de la tête est enlevée et tombant à droite et à gauche sur les épaules. Il y a tout à craindre pour sa vie. L’on se figure L’état de la malheureuse mère à cet horrible spectacle, elle arriva accablée de Lassitude, le visage baigné de larmes de tendresse et de douleur, et Le cœur partagé entre La joie d’avoir sauvé deux de ses enfans, et Le désespoir de voir le 3ème si cruellement déchiré.” ↩︎