A brief history of the beast of Gévaudan

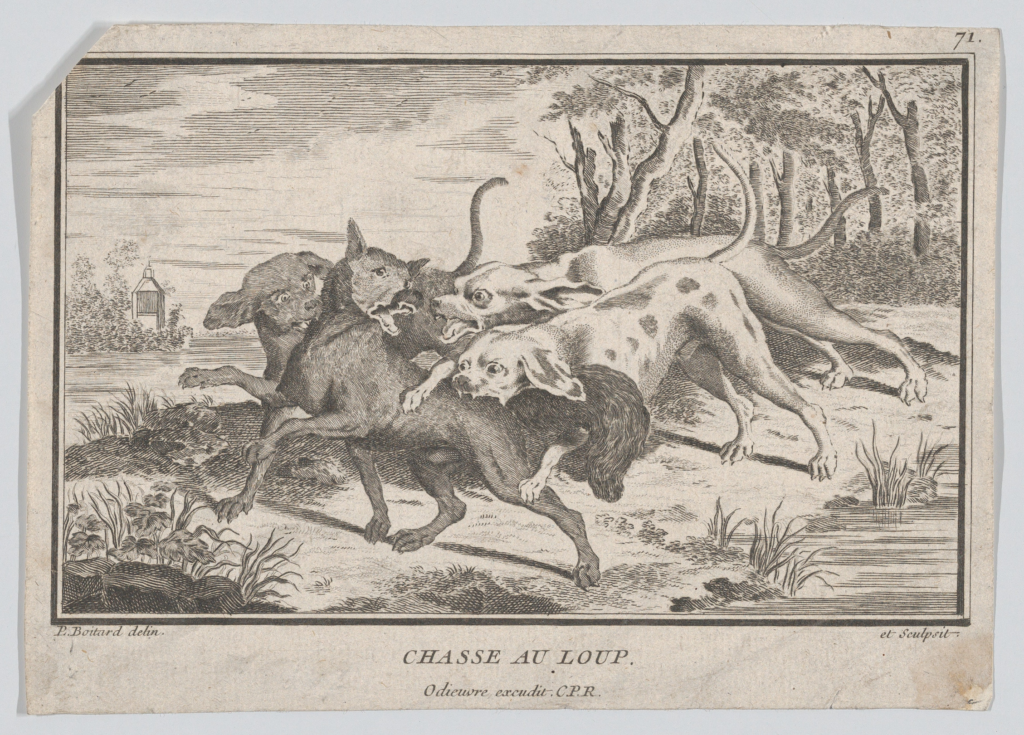

Then as now, Gévaudan was one of the least populated regions of France, its geography naturally suited to farming and shepherding, which of course, meant that its inhabitants were no strangers to the dangers of mountain predators, namely: the wolf.

Gévaudan as it exists nowadays is a primarily rural region of southern France, called Lozère, nestled in-between a series of mountains: the Margeride to the north, the Cévennes to the south, the Mont Lozère to the east and the Aubrac to the west. Its capital–also called prefecture–is Mende, which was also the primary town at the time of the beast. Modern-day Lozère encompasses the entirety of the old bishopric of Gévaudan, which itself was part of the pre-Revolution province of Languedoc.1

In the summer of 1764, a young thirteen year old girl is suddenly devoured, marking the first recorded death in the three-years drama that is about to unfold on the high slopes of the Margeride. The killer? Unknown, but everything points to the wolf. And yet, the death register is signed as follows: “In the year 1764, July 1st, was buried Jeanne Boulet, without sacraments, having been killed by the ferocious beast; here present Joseph Rivière and Jean Reboul.”2

And so it began. The young Jeanne Boulet was but the first victim (recorded) to fall prey to a mysterious and elusive killer, roaming Gévaudan and the adjoining Vivarais, soon followed by scores of others, primarily women and children, those most likely to be herding cattle up and down the mountains. The culprit was generally understood to be a wolf, what the peasants of the time called “loup carnassier”, which is to say: man-eaters. However, there were some who immediately theorized that la bête, as it soon came to be known, was something else entirely. But what?

This line of questioning has been the premise of many a movie and it is not the object of the present paper to answer it. So long after the facts and even with the best understanding of the subject, it would be impossible anyway. In any case, in July 1767, almost three years on the day since the first recorded fatal attack, a printed letter approved by a notary states, states black on white, that:

The monster of Gévaudan is no longer […]. Finally, Monsieur, peace rules again in the country; everything is back in order: terror has made room for joy. The children, whom until now were locked inside their houses with the greatest care, now guard their cattle in the pastures, and grown men are at liberty to take up more fructuous actions once more.3

All in all, in the three years during which la bête was active in the region, it allegedly killed between ninety and one hundred people, and wounded many others, who would ultimately survive and tell their stories, adding fuel on the already burning fire that became the myth of the beast of Gévaudan.

At the beginning of the 1760s, nothing seemed to indicate that the provincial region of France then known as Gévaudan, nestled amongst the mountains between Clermont-Ferrand and Montpellier in what is now modern-day Lozère, would one day become world-famous thanks to one particularly grim story: the beast of Gévaudan.

Wolf, hyena, hybrid, werewolf, serial killer, bloodhound, la bête has had many names and many faces. Famous for the gruesome carnage it left behind after an attack, the range of its misdeeds, and its elusive nature. Nobody can truly tell for certain whether the beast was finally caught or if it died, left, or never even existed as such, the mystery of its existence only serving to further amplify its fame.Was there truly a beast? If so, what was it and how did it manage to evade the hunters? Or was there foul-play? To what purpose? All these questions have been asked since the time the beast was prowling the countryside of Gévaudan; to no avail, although suspicions and theories ran rife at the time, and still do. Whatever it was, la bête captured the imagination not only of France, but of the entirety of Europe, at a time when superstition, religion, philosophy and science were swirling around each other in a tumultuous vortex, slowly but surely hurtling towards the inevitability that would, in twenty years’ time, become the French Revolution.

- On March 4th 1790, the department of Lozère was born when the new denomination of “department” replaced the old provinces. ↩︎

- Archives départementales de l’Ardèche, Saint-Étienne-de-Lugdarès, BMS 1757-1780, Acte mortuaire de Jeanne BOULET, 1er juillet 1764, vue 113/361. In French in the text: “L’an 1764 et le 1er juillet a été enterrée Jeanne Boulet, sans sacrements, ayant été tuée par la bête féroce; présents Joseph Rivière et Jean Reboul.” ↩︎

- BnF, 4-LK2-1888, letter “au sujet de la destruction de la vraie Bête féroce”, July 6th 1767. In french in the text: Le monstre du Gévaudan n’est plus […]. Enfin, Monsieur, la tranquillité règne dans le pays; tout rentre dans l’ordre accoutumé: la terreur a fait place à la joie. Les enfants, que l’on renfermait ci-devant dans les maisons avec le plus grand soin, conduisent avec sécurité leurs bestiaux dans les pâturages, et les hommes d’un âge mûr leur ont abandonné ces fonctions, pour en reprendre de plus solides et de plus fructueuses.” ↩︎