Recueil factice de pièces relatives à la bête du Gévaudan

formé par Gervais-François Magné de Marolles

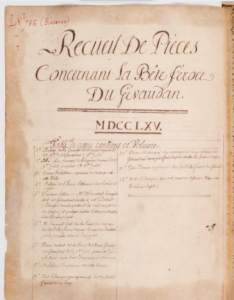

Written by Gervais-François Magné de Marolles in 1765, right as the attacks were unfolding in Gévaudan, the Recueil factice is one of the few contemporary manuscripts to touch on the subject of the infamous beast. It is held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, at the rare books reserve, under the shelf mark RES 4-LK2-786. But what is a “recueil factice”? And why did Magné de Marolles compile one on the beast of Gévaudan? What were his reasons?

According to the guidelines of the Agence bibliographique de l’enseignement supérieur, a “recueil factice” is a “bundle of documents (within the same binding, sheaf or box) assembled by a past or current owner” (see: guidelines). Additionally, it is by definition unique, since there can be no two completely identical copies of the same book. This last point essentially means that a “recueil factice” is not only precious for its mere existence–although that is certainly the case–but also because the choice of the documents contained within, as well as the order and manner in which they are assembled is a direct result of a conscious choice on the part of its author. In other words: the author or compiler (depending on the nature of the document itself) chose to (re)arrange specific documents, in a specific order, following a specific scheme entirely their own.

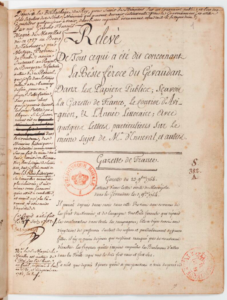

Even more interesting in the case of the Gévaudan recueil factice, is the fact that it is written largely by hand. Magné de Marolles took pains to copy newspaper clippings and extracts from personal letters by hand, interspersed with a few pages of printed material here and there, as well as a few prints depicting the Beast in action. In total, out of the 255 pages digitized by the BnF (not counting the prints, which mainly come at the end), 43 consist of printed material and the rest is entirely transcribed by hand. There are 11 prints in total, 6 of which are in color, the rest in black ink.

The author readily admits that his first instinct upon the redaction of these Mémoires, as he calls it, was not particularly patriotic. He was, before anything else, personally interested in the events of Gévaudan, and only belatedly realized that such a compilation of documents could be of interest to the “gouvernement” as well as other interested parties. That, presumably, was when he decided to donate the Recueil to the Bibliothèque du Roy, conscious of the fact that it would be the best place to preserve all of his hard work. Which, in turn, begs the question: why transcribe news clippings by hand?

Clearly, Magné de Marolles had these readily accessible in order to copy them, so why not simply bind them all up into a book? There are passages in the Recueil where some printed material is included. Why those and not others? These are questions that, unfortunately, only he can answer, and since we are unlikely to get an answer any time soon, we can only speculate.

Table of contents

Looking at the table of contents on the very first page, we also become aware of the author’s mindful organization, as well as his preoccupation with the future usefulness of his work. Under the head title, Recueil De Pièces Concernant La Bête Féroce Du Gévaudan, the date is clearly spelt out: M.D.C.C.L.X.V. i.e.: 1765. And under that comes the table of contents, with twelve different points, faithfully transcribed below:

1°. Relevé de la Gazette de France depuis le 23 9bre 1764 jusqu’au 1. 9bre 1765 | 10°. Précis Historique des ravages des Loups féroces du Gévaudan que j’ai fais d’après toutes les pièces ci-dessus |

2°. Du Courier d’Avignon depuis le 16 9bre 1764 jusqu’au 18. 9bre 1765 | 11°. Trois Poèmes imprimés sur la Bête féroce du Gévaudan |

3°. Deux Relations imprimées des ravages de cette Bête | 12°. XIV. Estampes qui ont paru en différens temps sur le même sujet |

4°. Relevé de l’Année Littéraire sur le même sujet | |

5°. Plusieurs lettres de Mr D’Enneval lorsqu’il étoit en Gévaudan écrites à Mr L’Intendant d’Alençon dans lesquelles il lui rend compte de ses chasses, et quelques autres Lettres particulières sur le même sujet | |

6°. Un Journal fait sur les lieux des ravages de la Bête féroce depuis le mois de Juillet 1764 jusqu’à celui de Juin 1766. | |

7°. Procès verbal de la Prise du loup féroce du Gévaudan le 20 7bre 1765 par Mr Antoine copié sur L’Imprimé à Clermont | |

8°. Relation Imprimée de cette Prise. | |

9°. Une Estampe qui représente la véritable figure de ce Loup. |

What the table of contents reveals at a glance is striking: Magné de Marolles compiled a wide array of sources together, from newspaper clippings (which are of particular interest to the present paper), to poems and “estampes”, or prints. Additionally, the manner in which he arranged his compilation also reveals how he personally approached each and every source. For example, the poems and prints come last, while the news pieces and other “relations” come first, including letters. Interestingly, what he calls his “Précis historique” also comes towards the end, when one might expect it closer to the beginning of the Recueil, not only in order to contextualize the events of Gévaudan, but also to assert the dominance of a historical point of view over the exaggerations of the press. But perhaps we can see in this particular choice, a wish to offer up what we would now call primary sources first, let the reader form their own opinions of them, before offering a more balanced perspective?

In any case, even if the validity of the sources–especially the newspapers–can and should always be questioned, the mere fact that someone decided to compile them together to form a volume dedicated not only to themselves but to a future audience, tells us enough about the importance of the events of Gévaudan. They were important enough to not only record, but compile and contextualize, even at the time, making this Recueil a valuable resource.

Below is a collection of different prints showed within the Recueil.

Gervais-François Magné de Marolles (1727-1795)

Born in 1727, Gervais-François Magné de Marolles was a French scholar and hunter, former infantry until he left the army and settled in Paris, where he dedicated himself to the study of bibliography, one of his interests. There are many publications under his name, some more important than others, but very little has generally been said or remembered about their author. Born in Tourouvre, he was the son of a notable family from Perche, who, after finishing his studies, joined the army. Very little is known about his time there, other than the fact that he became an officer, and that he most likely disbanded between 1760 and 1770, since his first printed works date back to around 1766.

Aside from his bibliographical pursuits, Magné de Marolles was also an extremely keen hunter, as his most well-known publication tells us: Essai sur la chasse au fusil, originally published in 1781. The Bibliothèque nationale holds two copies of various editions of this essay; one being the original edition and the other a much larger, later edition published in 1836, some forty years after the death of its author, called la Chasse au fusil.

According to A. Letacq in the 1923 edition of the Bulletin de la Société archéologique de l’Orne, although de Marolles’ works are now largely forgotten, he was however quite well-known in his time; both as a “scholar and a naturalist”. Given his own love for the hunt (a sentiment shared by most of the ruling classes of the time), Magné de Marolles’ attention to the attacks of Gévaudan likely stemmed from his own interest in hunting, leading him to compile his Recueil.

At the time of the events in Gévaudan, assuming that de Marolles had only fairly recently been decommissioned from the army, and since his Recueil is dated 1765-1766, it might in fact have been one of his first intellectual pursuits. At the time, he was staying in Alençon, in Normandy, province of origin of M. d’Enneval, a wolf hunter and one of the many dispatched to take care of the attacks. During that time, d’Enneval regularly corresponded with a man named Lallemant de Lévignen, giving us precious information about what was actually going on in Gévaudan, from the eyes of one unlikely to believe in either superstition or the supernatural.

Magné de Marolles’ Recueil factice has been used by every single writer who ever published anything related to the Beast of Gévaudan, highlighting its importance as a primary historical source, often derided as a collection of exaggerated tales rather than the assiduous and dedicated work that is was, carried out by a man with a very real interest in zoology and a keen mind unlikely to have been easily taken in by whatever myths were spreading about the nature of the beast.

![Hyenne_animal_féroce_qui_ravage_[...]_btv1b8409670k_1](https://alice-fournier.rarebook-ubfc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Hyenne_animal_feroce_qui_ravage_._btv1b8409670k_1.jpeg)

![(Recueil_factice_de_pièces_relatives_[...]_bpt6k1510133c_214](https://alice-fournier.rarebook-ubfc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Recueil_factice_de_pieces_relatives_._bpt6k1510133c_214.jpeg)

![(Recueil_factice_de_pièces_relatives_[...]_bpt6k1510133c_210](https://alice-fournier.rarebook-ubfc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Recueil_factice_de_pieces_relatives_._bpt6k1510133c_210.jpeg)