The state of the provincial press in the middle of the 18th century

As many changes as the 18th century brought, one in particular was to fundamentally change European culture by its sweeping popularity: the gazette. Gazettes and periodicals–two different things to the informed 18th-century readership–were not shining new toys; they’d already enjoyed popularity for well over a century in all European kingdoms and dominions.

The aim here is not to retrace the history of the French press, since the topic has been–and still is–exhaustively studied, but rather to briefly scratch its surface and touch on those particular topics of particular interest to our current subject.

Different types and categories of newspapers existed: from the Gazette de France, founded in 1631 by Théophraste Renaudot, which dealt with international political news, to the Journal des savants, a reference for all things literary or scientific, or the Mercure de France, a lighthearted newspaper specializing in anecdotal news of the beau monde. Despite their differences, however, these newspapers (and here the term is used as one would nowadays) had one thing in common, especially during the 18th century: to inform, to be useful and, most especially, to sell.1

But what sold, exactly? As Pierre Retat explains in his essay “Les gazettes: de l’évènement à l’histoire”, part of the larger study on 18th century newspapers Études sur la presse au XVIIIe siècle (1978):

From the infinite murmur of the world, they [the gazettes] retain only but a few echos, almost always the same, since they generally only deliver one type of facts […] those we expect and which take place within a system or a set of systems: […] the comings and goings of the king and his court, the communion of the queen, births and deaths in the upper ranks of society, troop movements, of generals and negotiators, the docking of a ship…2

Those were the events that characterized most of the newspaper production under the ancien régime, necessarily tied to its leaders. Interestingly, as Retat points out, even the “exceptional”, such as a military victory, for example, are not written down any differently than when reporting on the death of any given marquis: the gazette as it stands during the 17th and 18th centuries is superficial at best, narrating raw facts belonging to a transitory “present that disappears as it appears.” Even at the time, contemporary historians, such as 17th-century philosopher Pierre Bayle, for example, reviled the gazettes as nothing more than paper rags that never looked further than the tip of their noses, going so far as to call them the “burden and the plague of history.”3

Since then, historians have argued that the gazettes and other newspapers of the same ilk were in fact useful in that they recorded history, even if they did not comment on it, which was, in any case, the prerogative of intellectuals. They were, for lack of a better word, a necessary evil, working both for and against authority, chafing at the bit under the constraints of censorship and at the same time painfully aware of their precarious existence should they displease those in power.4

But all these newspapers we have hitherto mentioned had yet another thing in common: they were all parisian. What about the provincial press? What were the challenges it faced?

The provincial press

The three great parisian periodicals of the Grand Siècle–the Gazette de France, the Mercure and the Journal des Savants–had long prevented the true establishment of any provincial or local counterpart. As such, at first, in order to establish itself, the provincial press had to turn to alternative methods of communication, removed from the form of the “journal littéraire”, dominated by parisian newspapers.5 And thus was born the network of the Affiches.

The Affiches shared similar looks and contents in almost all provincial towns where they were published: generally printed in Petit Romain type, 9 points, set in two columns over four pages in-4° or in long lines over eight pages in-8°, the Affiches communicated various little “annonces”: commercial publicities and any other information that might be useful to the provincial population.6 Overall, in the second half of the 18th century, one could find the Affiches, annonces et avis divers in forty-seven provincial towns in France.7

Interestingly, although born in the printing offices of provincial towns (Bordeaux, Troyes, Reims, etc.), the city itself rarely figured within the title of the Affiches, sometimes due to rivalry between two major towns over their own countryside, and which should be the figurehead of any given Affiches, as was the case for Troyes and Reims in the 1770s, for example. But sometimes, the city itself could be depicted in the bandeau at the top of the first page, usually symbolically, subtly calling back to the center from which this new point of information came from.

Just like parisian papers, the Affiches in their provincial form were highly dependent on the demand and goodwill of their readers, and either thrived or withered, depending on their current relationship with their readership and their expectations. Mostly, what that readership demanded was fairly simple: news from home, not from Paris or other provinces. For most in these towns, the main point of interest was not what happened in the capital, but the preoccupations of their own terroir. And, as such, the Affiches also faced local censorship as well as the national one all newspapers bowed to. Additionally, the Gazette de France owned most of the copyright privileges of all the provincial Affiches and could decide to recall any of those at any point, so long as they were dependent on its privilege.

But even faced with potential censorship on all fronts, the Affiches still survived as long as the local elite was in their favor, especially since the middle classes (doctors, for example), found within their pages a way to communicate between each other and with the community at large. Apart from their role within provincial cities themselves, the Affiches also helped those cities to maintain and further their hold on the neighboring countryside, as well as smaller towns. And those smaller towns, in turn, helped circulate them in their own parishes.8 But before the Revolution, very few cities within the French territory could boast of their own “quotidien”, courtesy of the privileges, censorship and general control maintained by the larger parisian newspapers; in fact, prior to 1789, Bordeaux was the only one.

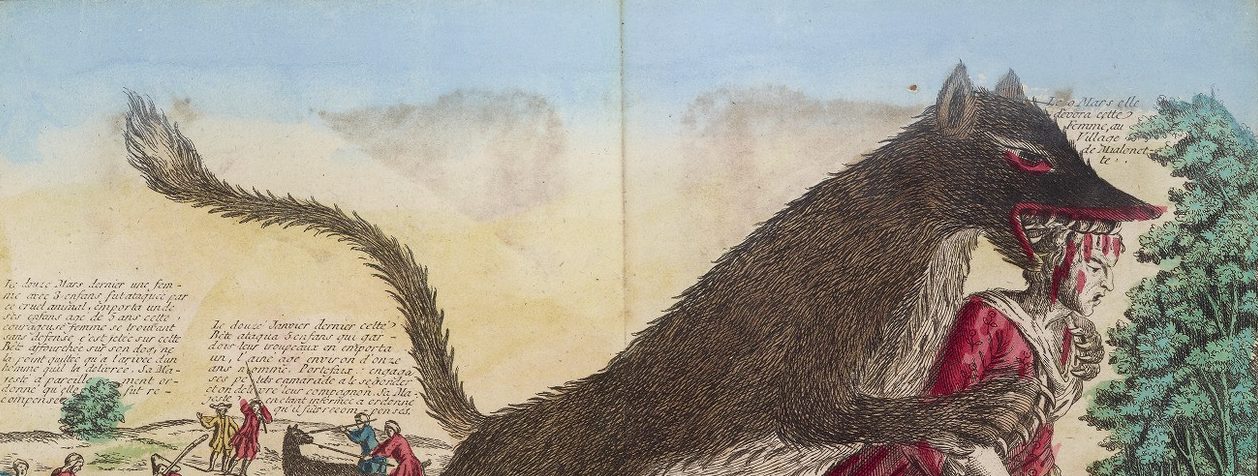

But what of Gévaudan? How did the story of the Beast come to be so well-known? Which periodicals played a major role in the circulation of the story? And how did they frame the story in such a way that the myth of La Bête is still famous to this day? The following chapters will address this particular question more thoroughly, but first, it is necessary to draw the picture of the main newspapers who took up the story, their own narrative(s), as well as their motives in their implication with the Beast of Gévaudan.

The provincial press and the Beast of Gévaudan: the three main players in the retelling of the provincial drama

In Magné de Marolles’ Recueil factice, three main newspapers are consistently cited as the main sources of information about the Beast : the Courrier d’Avignon, L’Année littéraire and La Gazette de France. All three of them were major players amongst the provincial and national press of the time, and all three of them were eager for more stories for their audience to sink their teeth into, especially since the end of the Seven Years War had left them high and dry content wise.

La Gazette de France

Older by a century than either the Courrier d’Avignon or L’Année littéraire, La Gazette de France, unquestionably, was the most important French newspaper of the time. Unlike the Courrier, it was also a parisian journal, not a provincial one, which meant that it dictated much of the rules provincial newspapers had to bow to in order to exist. Known first as the Gazette from 1631 to 1761, then as Gazette de France from 1762 to 1792, before changing titles multiple times throughout the 19th century, this journal survived up to 1915, boasting of the staggering number of 161 annual volumes between the years 1631 to 1791.

Until 1762, the Gazette remained within the hands of the descendants of its founding father, Théophraste Renaudot, but then became part of the ministry of Foreign Affairs, when it acquired the title it is today most known as: Gazette de France, published bi-weekly. It remained in complete control over its information networks until the French Revolution.9

Le Courrier d’Avignon

Created in 1733 by François Morénas, the Courrier d’Avignon was one the longest standing newspapers of the 18th century, running from 1733 to 1793. Its story is closely interlinked with the peculiar standing of the town of Avignon within the kingdom of France at the time. Avignon was the former seat of the so-called “Avignon papacy”, which lasted throughout the 14th century, and remained in the control of the papal states until 1791, when it became part of France again during the French Revolution. During the years of the Avignon papacy, seven consecutive popes resided in the city, and not in Rome, the historical seat of the Papacy.

At the time of the events in Gévaudan, the days of the Avignon Papacy were well and truly over, but the city, theoretically, remained in the control of the Papacy in Rome, and was therefore not a part of the kingdom of France. This also meant that the gazettes, couriers and affiches located in Avignon existed independently of the national censorship laws–although it was still subject to those of the papal states.10 Additionally, in 1740, the Courrier d’Avignon managed to obtain a special subscription contract license drastically lowering the postal taxation (that all provincial press was liable to), skyrocketing its popularity amongst the local, national, and international readership.11

L’Année littéraire

Founded by Elie Catherine Fréron in 1754, L’Année littéraire was one of the most important newspapers of its time, not only due to its success but by the sheer diversity of its subjects. Published every ten days or so, full of a variety of articles (generally anonymous), L’Anné littéraire was more than just its title. Although it was, first and foremost, a newspaper that dealt with literature, Fréron also had to bow to the zeitgeist of the time, when the scientific and philosophical questions of the Enlightenment were making themselves known.12

L’Année littéraire was also known for its polemical status amongst the Enlightenment philosophers, often taking up arms against Voltaire, Diderot and others, including Rousseau. The very nature of the journal was oxymoronic, according to Jean Balcou, who states the following

[…] The profound interest manifested throughout by the public opinion for L’Année littéraire comes from, perhaps, the following: that, seduced by the dynamism and the spirit of the Lumières, but worried about the revolutionary reality they embodied, it found there its own dilemma.13

After Fréron’s death in 1776, his widow and his son took up his mantle and continued the publication of the journal, with a more marked interest in literature–at least more so than under Fréron the elder. But the general anti-philosophical stance adopted by the journal in its early days remained, and so did an interest in general fait divers.

Together, as three of the most important national newspapers, Le Courrier d’Avignon, L’Année littéraire and La Gazette de France took up the story of the Beast, relaying it to their own audiences, ensuring not only its fame amongst their contemporaries through their own vast networks, but also actively participating in the creation of a rural legend, well-known to this day.

- Maud Le Quellec, “Chapitre XI. Les visées de la presse au XVIIIe siècle,” in: Presse et Culture dans l’Espagne des Lumières, Casa de Velázquez (2016): 317-326. ↩︎

- Pierre Retat, “Les gazettes: de l’événement à l’histoire,” 23-38, in: Robert Favre, Michèle Gasc, Claude Labrosse and Pierre Retat, Études sur la presse au XVIIIe siècle, (Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, 1978). In French in the text: “Du murmure infini du monde, elles ne retiennent que quelques échos, presque toujours les mêmes, car elles ne livrent généralement qu’un type de faits, intégrables, ceux que l’on attend et qui prennent place dans un système ou un ensemble de systèmes; l’événement, ce sont les déplacements du roi et de la cour, la communion de la reine, les naissances et les morts dans la société noble, les mouvements de troupes, des généraux ou des négociateurs, l’arrivée des navires dans un port…” ↩︎

- Pierre Bayle, “Lettre 65: Pierre Bayle à Vincent Minutoli,” Correspondance de Pierre Bayle, accessed January 15th 2024, https://bayle-correspondance.univ-st-etienne.fr/?Lettre-65-Pierre-Bayle-a-Vincent. ↩︎

- Here Retat cites the work of Myriam Yardeni, “Journalisme et Histoire contemporaine à l’époque de Bayle,” History and Theory 12, no. 2, (1973). ↩︎

- Gilles Feyel, “La presse provinciale au XVIIIe siècle: géographie d’un réseau,” Revue Historique 272, fasc. 2 (552), (Octobre-Décembre 1984): 353. ↩︎

- Idem, 356. ↩︎

- Gilles Feyel, “Ville de province et presse d’information locale en France, dans la seconde moitié du XVIIIe siècle,” 11-36, in: Christian Delporte (dir.), Médias et villes (XVIIIe-XXe siècle), (Tours, Presses universitaires François-Rabelais, 1999). ↩︎

- Gilles Feyel, “La presse provinciale au XVIIIe siècle: géographie d’un réseau,” 368-369 ↩︎

- Encyclopédie Universalis, “Gazette La, puis Gazette de France,” accessed May 9th, 2023, https://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/gazette-gazette-de-france/. ↩︎

- Gazettes européennes du 18e siècle, “Courrier d’Avignon,” accessed May 9th, 2023, https://www.gazettes18e.fr/Courrier_Avignon#C. ↩︎

- Pierre-Yves Beaurepaire, “Chapitre II: L’Europe des Lumières: un espace de circulation et d’échanges”, in L’Europe des Lumières, (2018), pp. 43-82. ↩︎

- Dictionnaire des journaux, “L’Année littéraire,” accessed May 9th, 2023, https://dictionnaire-journaux.gazettes18e.fr/journal/0118-lannee-litteraire. ↩︎

- Idem. ↩︎